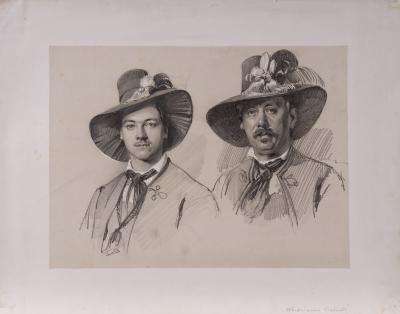

У XVII ст. поховання визначної шляхетської особи супроводжувалося церемонією, в якій визначальну роль виконував портрет небіжчика. Натрунні портрети малювалися «ad vivum» (як живий) на срібній, мідній або бляшаній пластині. Вони мали шестикутну форму, що було зумовлене їх розміщенням на торці труни. У XVII ст. це була строго шестикутна форма, у XVIII ст. в основі залишився той самий шестикутник, що набув ускладненого баркового профілю. Головною вимогою у таких портретах була якомога більша схожість його з портретованою особою. Маляр не мав права ідеалізувати, його завданням була детальна передача індивідуальних рис особи. На портреті змальовано обличчя жінки – людини із сильним і владним характером. Її повновиде, рум’яне обличчя, наближене до глядача, сповнене життєвої енергії. Гордий погляд карих очей, ніби у посмішці складені вуста та піднята голова підкреслюють самовпевненість зображуваної. Реалістично змальовані прикраси: дорогі сережки у вухах, низки перлів на шиї, егрет у волоссі. Лише обрамлення портрета свідчить про його епітафійне призначення. Білецький вважає, що зображувана жінка нагадує Софію Радзивілл, яку змалював В. Кліковський 1740 р. (ЛІМ).