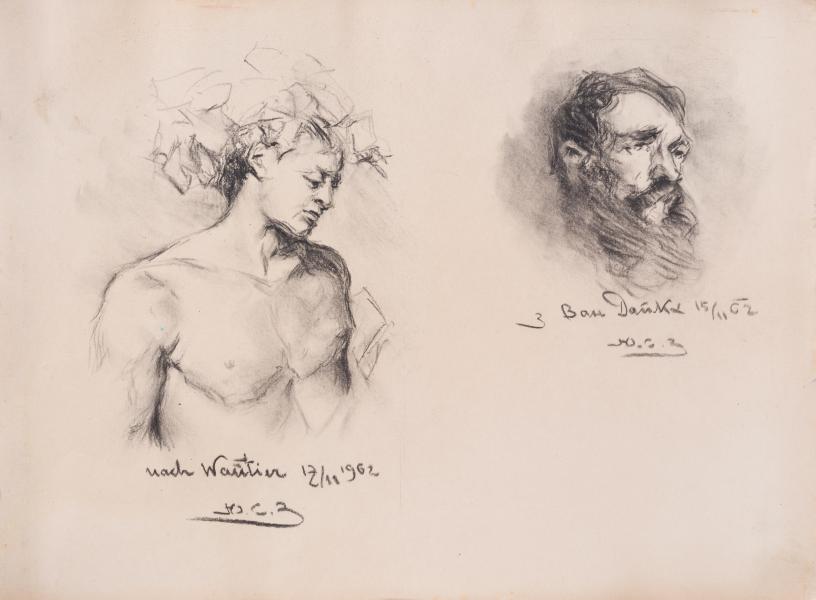

Among Yulian Zaiats' drawings created in 1962, two works are noteworthy, representing the author's interpretation of classical imagery characteristic of European painting from the 17th to the 19th centuries. Both images are copies and partly free variations based on the works of old masters. This is not only about practising technique, but also about attempting to gain a deeper understanding of the plastic, thematic, and psychological aspects of the classical image. In these drawings, Zaiats acts not only as an attentive copyist but also as a researcher who seeks inspiration for his own artistic thinking in the legacy of the old masters. The first drawing is a bust portrait of a young man with a bare torso, leaning in a thoughtful, slightly melancholic pose. His head is crowned with a wreath of grape leaves, hinting at the mythological or allegorical nature of the image. Perhaps this is a participant in a bacchanalia or even Bacchus himself in a moment of intimate reflection. This image is profoundly different from the theatrical bacchanalian scenes dominated by expression, chaos, and movement. On the contrary, we see a moment of concentrated silence, as if after a noisy celebration or before its beginning. Zaiats models the forms of the face and body with particular care, paying attention to the smooth transitions of shadows and lines, as well as the play of light on the collarbone, neck, and chest. The mixture of softness and graphic rigour gives the figure not only a physical but also a psycho-emotional presence. This is not just a training copy, but rather an interpretation of an image that conveys a sense of longing for the ideal, for a lost myth, or the profound essence of human nature. The second drawing, a three-quarter view of a bearded man's head, was probably based on one of Anthony van Dyck's portraits, although the exact source has not been established. However, the very choice of van Dyck as the basis for the drawing is telling, as he is a master of aristocratic portraiture, restrained nobility, and deep inner characterisation of the image. Zaiats, while preserving the general stylistic features of the original, does not copy it literally, but creates a self-sufficient graphic image in which considerable attention is paid to the rhythm of the lines, the structure of the beard, and the deep gaze. The visual mass of the beard and hair is balanced by soft chiaroscuro on the forehead and cheek. There is no excessive decorativeness in the image; on the contrary, restraint and plastic clarity create an aura of psychological depth. The slightly raised head and inward gaze lend the portrait an ascetic dignity reminiscent of Christian or Stoic ideals of masculinity. Both works are evidence of a special stage in Yulian Zaiats' career, as 1962 was a time when the artist had already established himself as a master, capable of critically rethinking traditions and weaving them into his own creative strategy. Therefore, these are not just exercises in craftsmanship, but rather intellectual dialogues with the past, a search for deeper layers of imagery that could nourish his further artistic work. Presumably, these images, physically expressive yet internally focused, served as a kind of matrix or reflective points through which the author contemplated human nature, dignity, strength, and fragility. In this context, the drawings of 1962 take on greater significance, allowing for a better understanding of the artist and the formation of his own artistic language.