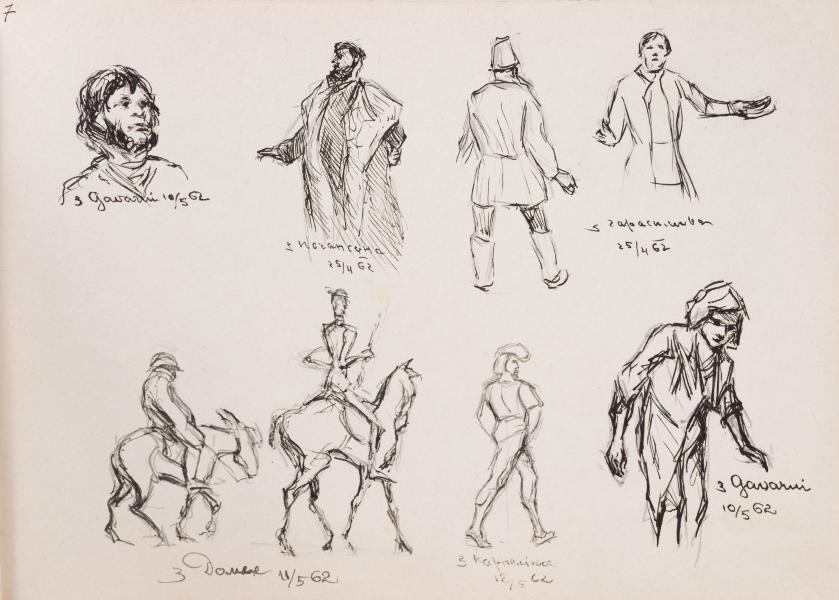

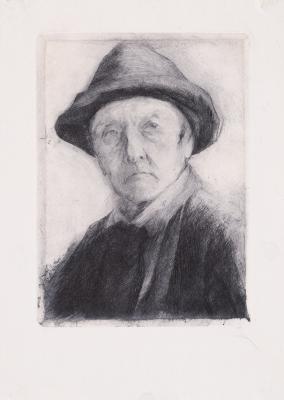

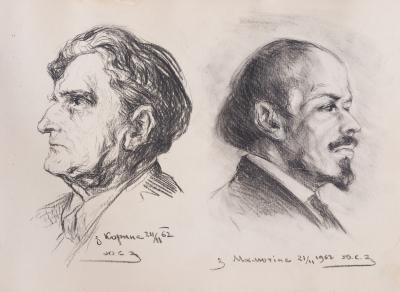

The sheet presents a group of sketches made with analytical interest in characters from the works of European and Soviet artists of different eras. It is a kind of visual study of characters, in which the author seeks not only to capture the external features of faces, but also to convey the psychological tension, grotesque or dramatic expressiveness inherent in the sources. Among the identified images are Don Quixote and Sancho Panza as interpreted by Honoré Daumier with the master's characteristic mixture of satire, humanism, and tragic irony. Both characters are read not only as figures from a literary work, but also as generalised images of people on the verge of the comic, tragic, and heroic. Next are the characters of Paul Gavarni (the first in the front row on the left and the last on the right in the second row). The line here is lighter, poster-like, with elements of graphic stylisation close to the illustrative tradition. The image is conveyed with sympathy, some detached irony, and attention to detail, particularly in the work on the plasticity of the man's body, the curve of his neck, and the position of his shoulders. The third block consists of fragments from compositions of the Soviet period, in particular, a portrait of a red-bearded (in the original) man in a fur coat from Borys Johanson's famous painting "Soviet Court". The author interprets the image not as part of a genre scene, but as a self-sufficient character. The figure, which likely belongs to Oleksandr Harasymov's work, is drawn in the same manner. Perhaps these are types of peasants or collective farmers, characterised by a monumental calmness and a rigid, stoic build. The second-to-last figure is a portrait of an unknown character, probably from the works of an artist of the late 19th to early 20th centuries (the name is unclear, possibly "K(P)...yuka"). The portrait is intimate in nature, possibly with elements of realism. Light hatching and sparse lines only allow the anatomy of the face to be outlined, but the gaze retains its individuality. The manner of drawing is generally clear and confident, with slight variations in line depending on the source. In the case of O. Domier and P. Gavarni, the style is slightly lighter and more graphically decorative, whereas in the case of Soviet images, it is heavier, with an attempt to convey volume and tonal mass. It remains clear that these drawings are not exercises in copying, but rather reflections on the language of the image in different cultural and historical contexts. The author works consciously, using these types to study the characteristics of the visual code from satirical to monumental, from romantic to everyday. The captions under some of the images testify to the systematic nature of the work (dates: 1962, identified names), which allows us to consider the letter as part of a broader cycle of graphic explorations by the artist in his mature years, with an emphasis on the study and reconstruction of artistic languages of different eras.